Part II

Fellow tourist: I have a Kindle with [title of well-known book criticizing North Korea] on it. Should I move it to a hidden folder?

Tour guide: They know where to look and how to access hidden folders. You’ll want to delete it.

Same tourist, five minutes later: I’m brining a laptop with a copy of The Interview on it…

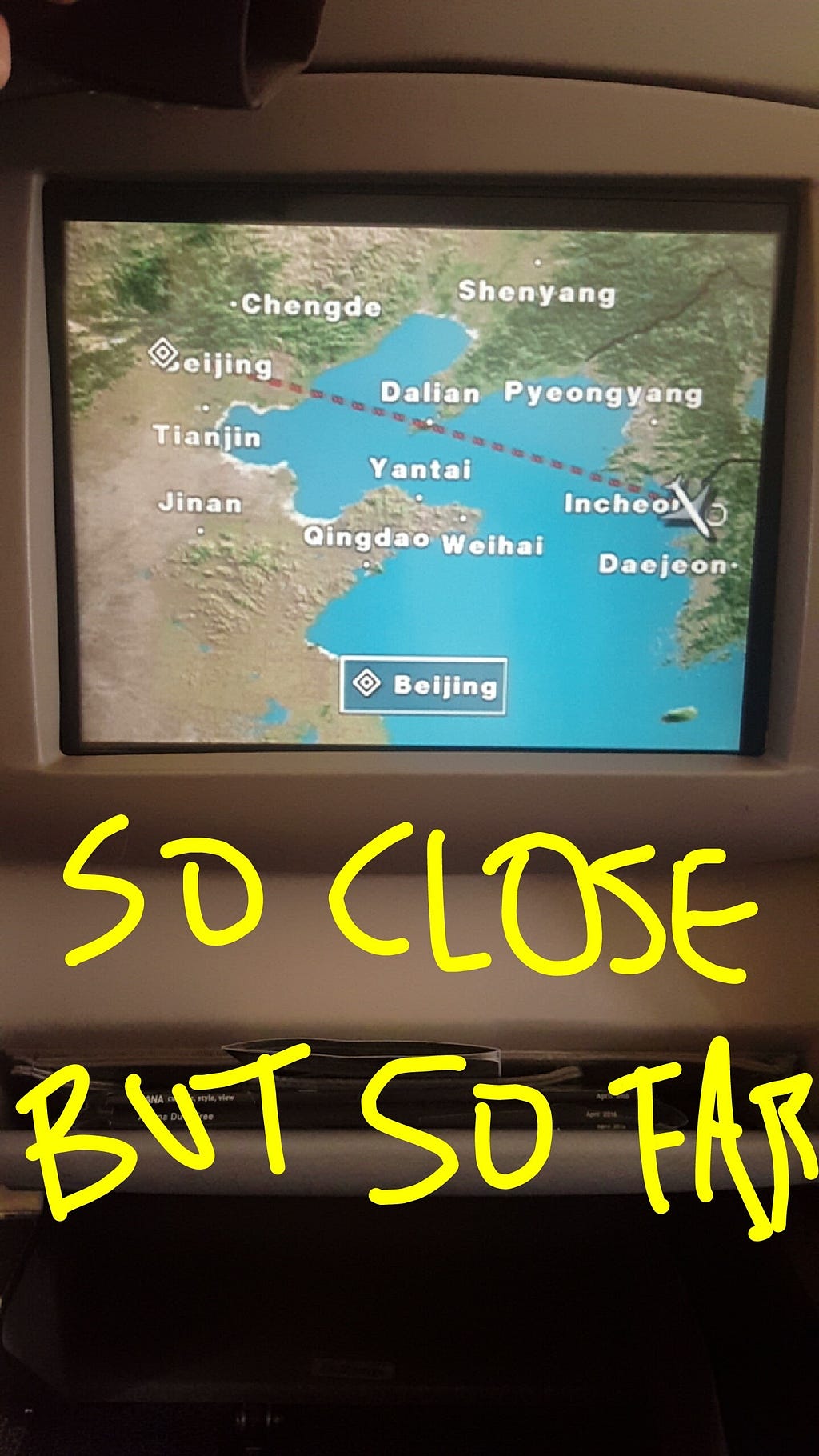

Seoul is 194 kilometers from Pyongyang. Let’s call it 200. I’m trying to be a good global citizen and use metric but I need miles for this one. So…move the decimal…multiply by six. 120 miles! A two hour drive. A 30 minute flight. So close.

But you can’t get there from here.

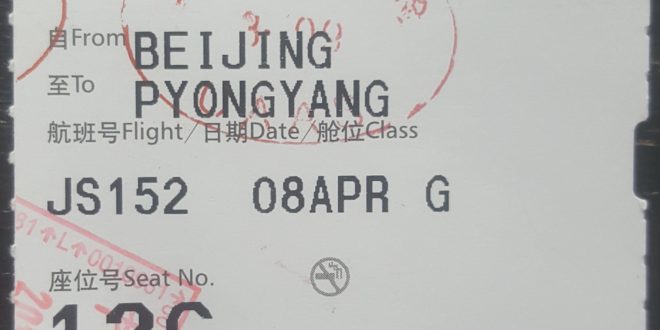

China is the last point of departure for most trips to North Korea. On Thursday April 7 I left Seoul for Beijing and a mandatory thirty minute rules and regulations briefing. Only then would the tour company allow us to board Friday morning’s flight to Pyongyang. I arrived 45 minutes early to the 4pm session. There wasn’t enough time to sight-see in Beijing, and I wanted to meet the people I’d be spending the next three days with. Ulterior motive: scout out potential trouble makers.

By definition, everyone going on this trip is a risk-taker. You can read everything written about travel to North Korea, pack according to its rules and plan to exercise the most cautious behavior. There’s no guarantee anyone else will. And that’s the best assumption to make. You do you. The wild card is everyone else.

Here are the travelers I met on the trip. These groupings are not mutually exclusive:

- Travel lifers Travel is literally their life. e.g. there was a Texas-born woman in my group who’s six month honeymoon was spent hiking from Mexico to Canada; she now lives in China with her husband who leads photo-expeditions to Mount Everest base camp. She travels to recruit exploited Chinese women and offer them a new life making jewelry. Amazing. Travel lifers often shoulder strappy 45 liter hiking backpacks as carry-on luggage and wear cargo pants that unzip at the knees to become shorts. This is a good crew to stick with, their travel prowess is aspirational. They know their way around an airport, pack really useful things, like flashlights, lesser travelers would never think of (North Korea and the Yanggakdo hotel are notorious for power outages), and they do a great job adapting to local customs and laws.

- Travel hobbyists While they also place high-value on travel, it is a leisure activity and likely a status symbol. Generally of a comfortable socio-economic status, this set is more corporate than nomad. Some hobbyists travel like lifers, but most stay in resorts, are very reliant on the concierge, and don’t consider public transportation an option. This concerns me.

- Political pundits Mostly Canadians. Extremely well versed in the global political scene. The further north they lived the more opinionated they were. The sample size wasn’t large enough to establish a statistically significant relationship, however. Political discussions often escalate and passionate participants lose sense of time and place. Heated debates invariably reference some socialist/facist/communist regime, invoking an off-line derivative of Godwin’s law. Too dicey.

- Fringers You get the strong sense they chose this trip over paying rent. Their back story is filled with holes and when you ask them what they do for a living they say things like, “I work with my hands.” It’s hard to get a read on them and that scares you. This trip was a whim and their North Korea knowledge is no further along than Stage 2. Fringers don’t have much to lose and consequently make unsettling life decisions.

- The average traveler has a natural curiosity about the world, reads at minimum 30% of the destination’s WikiTravel entry and, most importantly, exhibits a healthy skepticism and anxiety about visiting North Korea. This was most of the tour group. Me included.

- Bros I knew there would be bros. Finding them was the ulterior motive of my ulterior motive.

Besides the in-flight meal, the most notable thing about the flight to Pyongyang is the mix of emotions that hits when you settle into your seat. Excitement dominates. This is finally happening! You’re going to experience for yourself what you’ve been reading about and what people have been warning you of for almost a year. What will be true? What’s won’t? What new things will you discover for yourself? Anxiety fills whatever emotional space is left. The cabin door closes and there’s no turning back. You’re in North Korea’s hands now. Will the research pay off and keep you out of trouble? Is North Korea going to be who you thought they were going to be? What’s in this sandwich?

I’m not sure the make and model of our Russian aircraft, but it wasn’t new. The seating configuration in our cabin was 3×3. I was in an aisle, seated to the right of a professional marathoner from Africa. It’s common for race organizers to subsidize participants’ travel and entry costs. Professional runners lend competitive credibility to the event and diversity makes for good PR. This was going to be Jackie’s first race in a few years. I’d have enough time after finishing mine to make it into the stands and watch the end of the full marathon. Neither of us ate the sandwich.

Our first taste of North Korean censorship came on the long taxi to the gate. The shock from the very hard landing forced open an overhead panel about ten rows ahead of us. A safety wire prevented it from falling into the laps of the passengers below. Almost instinctively, the girl seated in the opposite aisle snapped a picture of the malfunction. This drew the attention of the male North Korean flight attendant. He got up calmly from his seat, which he changed three or four times during the flight, and examined the girl’s phone. I don’t know if he deleted the snap or not. It didn’t matter. We got the picture: we were in North Korea.

Also published on Medium.